Is Coronavirus driving a recession, depression or an economic hit like no other?

Key points:

- Global share markets have fallen into a bear market, but whether this turns out to be long or short depends on how long the hit to the economy from coronavirus lasts.

- There are big differences between the current disruption to economic activity – which could be very deep in the short term – and past recessions and depressions.

Introduction

Global and Australian shares have fallen well beyond the 20% decline commonly used to delineate a bear market. From their highs to their recent lows major share markets have had roughly 35% falls as investors moved to factor in a big hit to growth from coronavirus shutdowns.

Recession now looks inevitable and they tend to be associated with deep and long bear markets, but now there is even talk of a depression suggesting an even deeper bear market. In reality, there are big differences now compared to past recessions and the Great Depression, so it really looks like an economic hit like no other with very different implications for the bear market in shares.

But let’s first look at past bear markets as they provide some lessons for investors regardless of the cause.

There are two types of bear markets in shares

“Gummy” bear markets with falls around 20% meeting the technical definition many apply for a bear market but where a year after falling 20% the market is up, and “Grizzly” bear markets where falls are a lot deeper and usually longer lived.

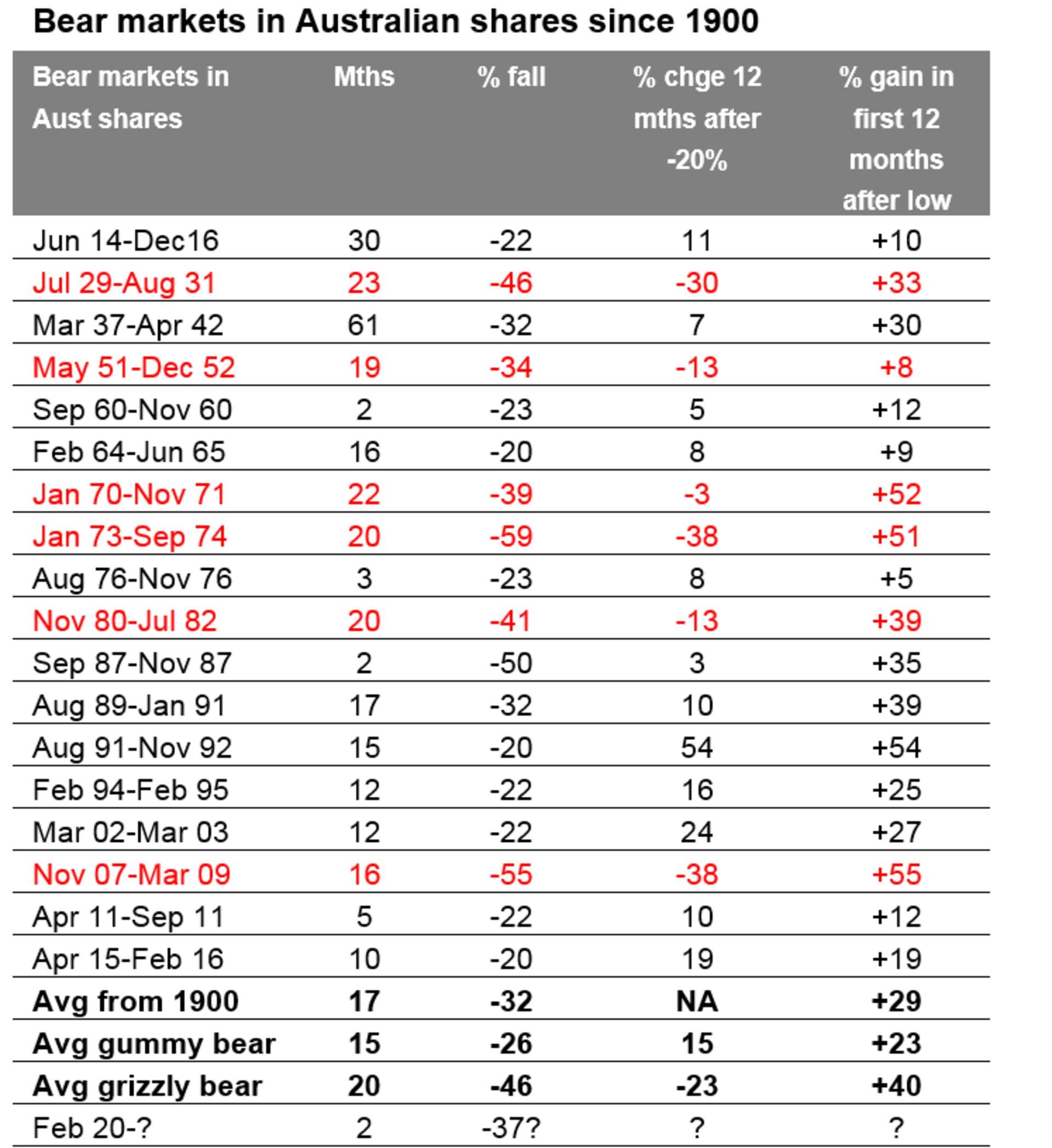

Grizzly bears maul investors but gummy bears eventually leave a nicer taste (like the lollies!). The next table takes a closer look at bear markets. It shows conventionally defined bear markets in Australian shares since 1900 – where a bear market is a 20% decline that is not fully reversed within 12 months.

The first column shows bear markets, the second shows the duration of their falls and the third shows the size of the falls. The fourth shows the percentage change in share prices 12 months after the initial 20% decline. The final column shows the size of the rebound over the first 12 months from the low.

Based on the All Ords. Where a bear market is defined as a 20% or greater fall in shares that is not fully reversed within 12 months. Source: Global Financial Data, Bloomberg, AMP Capital

Since 1900 there have been 12 gummy bear markets (in black) and six grizzly bears (in red). Several points stand out.

- First, gummy bear markets tend to be shorter and see smaller declines around 26% compared to 46% for the grizzly bears.

- Second, the average rally over 12 months after the initial 20% fall is 15% for the gummy bear markets but it’s a 23% decline for the grizzly bear markets.

- Third, the deeper grizzly bear markets are invariably associated with recession, whereas the milder gummy bear markets including the 1987 share market crash tend not to be. All six grizzly bear markets, except that of 1951-52, saw a US or Australian recession (or both), whereas less than half of the gummy bear markets saw recession. It’s also the case for the US share market.

- Finally, once the bear market ends the rebound is strong with an average gain of 29%. Trying to time this is hard with many who get out on the way down finding they don’t get back in until the market has risen above where they sold.

Recession versus depression or something else?

So, one of the key messages from history is that if we have a recession then the bear market will likely be grizzly and severe with markets even lower than they are today in 12 months’ time.

It’s not necessarily that simple though as the shock this time is very different to those seen in the past. But first the bad news. Recession now looks inevitable. There is now even talk of “depression”.

While there is a huge unknown around how long it will take to control the virus, and hence how long the shutdowns will last, it is looking clear that the short term hit to GDP will be deeper than anything seen in the post WW2 period hence the increasing references to the pre-war depression:

- Chinese business conditions PMIs for February fell an unprecedented 24 points due to shutdowns starting 23rd January. Consistent with this Chinese economic activity indicators are down 20% from levels a year ago. Chinese March quarter GDP could well be down 10% or so.

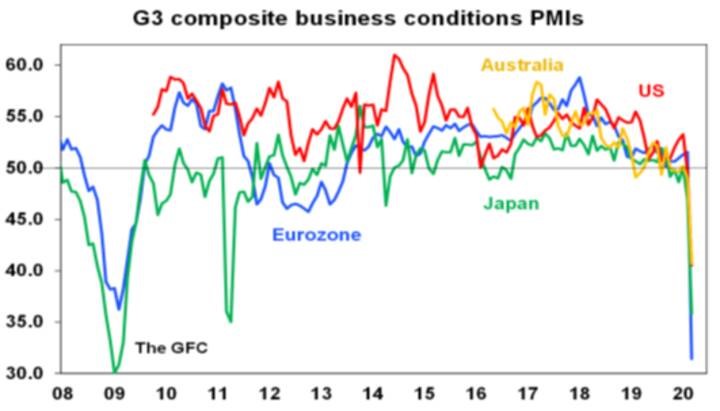

- Business conditions PMIs for the US, Eurozone, Japan and Australia all plunged in March as lockdowns ramped up. The average decline for these countries composite business conditions PMIs was an unprecedented 12 pts. This takes them below levels seen in the GFC. And the shutdowns have only just started so further falls are likely in April. So like China, developed countries could conceivably see 10% or so falls in GDP centred around the June quarter.

- The shutdowns will see a large hit to roughly 25% of the Australian economy, particularly accommodation and culture, retailing and real estate.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

Big differences between past recessions and depressions

But while the slump in economic activity may be deeper than anything seen in the post war period, depression may not be the best description.

Most definitions of depression focus on it being over several years and seeing a very deep fall in GDP compared to a recession which is shorter and shallower.

The current hit to economic activity may be very deep but it won’t necessarily be longer than past recessions. And there is good reason to believe that if the virus comes under control in the next 2-6 months, and we minimize the collateral damage from the shutdowns, the hit to activity may be shorter.

There are big differences between the current situation and that of past recessions and Great Depression of the 1930s:

- First, recessions and The Great Depression (which saw GDP contract by 36% over 4 years and unemployment rise to 25% in the US and GDP fall by 9.4% in Australia with a rise in unemployment to 20%) were preceded by a period of excess in terms of investment, consumer discretionary spending, private debt growth and inflation that had to be unwound. This time around there has been no generalised period of excess and there has been no large-scale monetary tightening to bring on a downturn.

- Second, monetary policy was tightened in the lead up to past recessions and in the early phase of the Great Depression, whereas global monetary policy was eased last year and that easing has accelerated this month with rate cuts, a renewed ramp up of quantitative easing (QE), and central banks around the world establishing various ways to ensure credit flows to the economy. In the 1930s banks were simply allowed to fail. Now they are being supported by ultra-cheap funding. Much of this owes to the GFC experience which has made it easier for central banks to now ramp up QE and introduce support mechanisms.

- Third, going into the Great Depression fiscal policy was tightened to balance budgets whereas in the last month we have seen massive and still growing global fiscal policy stimulus swamping that of the GFC. The latest US fiscal stimulus package alone is around 9% of US GDP.

- Fourth, there has been no trade war such as the Smoot-Hawley 20% tariffs on US imports that were met by global retaliation and saw global trade collapse in the 1930s.

The bottom line is that while we may see the biggest hit to global and Australian GDP since the 1930s thanks to the shutdowns, there are big differences compared to the Depression suggesting that a long drawn out global downturn is not inevitable. Basically, it’s a disruption to normal activity caused by the need to stay at home.

In fact, growth could rebound quickly once the virus is under control and policy stimulus impacts. Which in turn should benefit share markets and could see this latest bear market turn into a gummy bear market rather than a grizzly bear market.

Of course, at this point we are still waiting for convincing evidence that markets have bottomed. And the key is that the number of new cases of coronavirus starts to slow and that collateral damage from the shutdowns are kept to a minimum.

Source: Dr Shane Oliver, AMP Capital March 2020